My picture is about kids not able to speak. They are held quiet and basically if they do talk, bad things happen to them. The coat over it means a new start. By: Z.D. Age: 12

My picture is about kids not able to speak. They are held quiet and basically if they do talk, bad things happen to them. The coat over it means a new start. By: Z.D. Age: 12

The Power of Youth Voice at St. Stephen’s B-SAFE Summer Program

St. Stephen’s B-SAFE Program (The Bishop’s Summer Academic and Enrichment Program) in urban Boston is a vibrant summer program that provides 650 city children with affordable, high quality academic and enrichment opportunities as a way to help them feel “safe, big and connected.” The program also hires approximately 80 adult staff and 160 local teenagers, providing meaningful employment and mentoring opportunities for many city youth. This model creates “circles” of support, with younger campers having the opportunity to later move up to positions of leadership. The program runs out of six sites, serving children in the neighborhoods of Dorchester, Mattapan, Roxbury, Chelsea and the South End.

Beyond its powerful youth leadership model, the underlying spirit of the B-SAFE program is what makes it truly transformative. Central to the philosophy of B-SAFE is an understanding that social justice work is important and needed. The larger B-SAFE community — which includes an extensive system of partner parishes and communities throughout Greater Boston, as well as partnerships with five employment agencies/programs — embraces the core belief that we should not shy away from social empowerment, community betterment and change.

Under the compassionate leadership of Rev. Tim Crellin and Rev. Liz Steinhauser, the B-SAFE staff recognizes that the young people they serve are from communities faced with serious issues such as gun violence, poverty, incarceration and racism, yet they are not often given the opportunity to process these issues, to express their views or to imagine radically different alternatives to the status quo. The underlying ethos at B-SAFE is that young people deserve to be brought into conversations about the social problems they face and be given the opportunity to express their views, openly and safely, within supportive community.

In this sense, the program is inherently counter-cultural in that it encourages young people and teachers alike to question and challenge existing power structures, both within their immediate communities and beyond.

YLC Students at B-SAFE’s Epiphany site in Dorchester.

YLC Students at B-SAFE’s Epiphany site in Dorchester.

Implementing a social justice art curriculum, with a focus on the issue of gun violence

As part of the B-SAFE art program this past summer at the Epiphany and St. Stephen’s sites, I implemented a social justice arts curriculum with children, grades 5-8. I want to record this experience because I was moved by the power of the artwork my young students created and inspired by the directness of their messages. I do so also because, given the grim national news of July — punctuated by multiple gun violent killings of both black men and police alike — this work has a particular relevance to what is going on in our country today. With that background as context, I was asked to create an art curriculum with a focus on social justice and with a particular focus on gun violence.

When I was initially contacted to begin formulating my art curriculum for the summer, Kemarah Sika (Academic Director at B-SAFE) described the primary learning goals for the art program as specifically rooted in issues of social justice and community building. She hoped that students would learn to “celebrate and acknowledge what is positive and unique about the community they live in” while also being able to identify the injustices around them, express their feelings about these injustices and be able to imagine a more just future beyond them. Developing a critical sense of both pride and self-awareness is central to these learning goals. As Kemarah put it, “the majority of students do not even know that what they have is different from what other people have.”

More specifically, I was asked to address the issue of gun violence. Sitraka St. Michael, one of my fellow, inspirational, teachers at B-SAFE and a current graduate student at Harvard Divinity School, had drafted the essential questions: “How can the art curriculum empower B-SAFE participants to cultivate a critical consciousness about gun violence? How can they express the emotional toll that gun violence enacts and use their imaginations to transform the realities of gun violence?” His thoughtful curriculum suggested looking unapologetically at the issue of gun violence and asking students to consider their own emotional response.

Ideation through both individual reflection and group collaboration

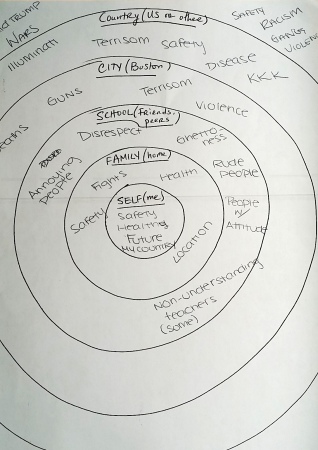

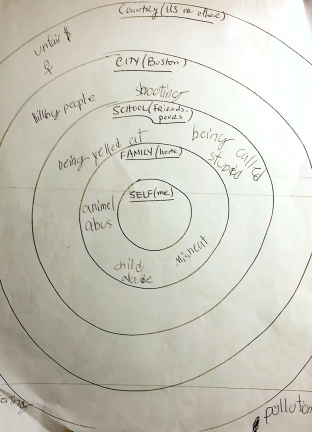

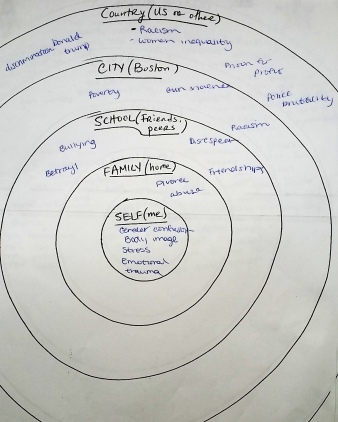

This was a challenge for me. As their teacher, I was wary of leading in with “gun violence” as a theme. Rather, I was interested to see what issues would come forward naturally, without specific input from my part. To begin the project, I engaged students in brainstorming activities. Students created visual word maps, documenting the issues important to them, first as individuals and later as a group. We discussed how issues could be social (about people), political (about power), economic (about money), or environmental (about nature). We also discussed how “community” starts small (with home and family) and moves out to include school, city, state, country, and world. Students identified what issues were important, within each of these concentric circles. They first shared out individually, to the group, and then we pooled the responses into one, larger visual word map for each class.

Here are four examples of individual student responses, using the concentric circles of community, from students ages 9-12.

Here is an example of the compiled data into one, larger word map. Again the question was: What issues/problems in your community do you care about?

This particular brainstorm was from Group 3, by students in grades 6 and 7

This particular brainstorm was from Group 3, by students in grades 6 and 7

After each class made their own word maps (in which the words get bigger the more times they are mentioned), we looked at them as a group and discussed them. I asked them open-ended questions like: “What comes to mind when you look at your class’s word map?” “Is there anything you want to talk about?” They immediately raised their hands, and had a lot to say, especially about the current presidential campaign. In discussion, I was particularly struck by how terrified many of the students were of Trump’s candidacy, asking me repeatedly: “What will happen if he becomes president?” There was no doubt that he looms large in their young minds like some frightening specter. They did not hesitate to tell me that he was a “racist” and that he wanted to “stop immigration” or “send us all away.” I found it interesting that even among children as young as 9 and 10, they had a visceral, profound fear of Trump and what he represented to them. This was good to talk about. Some of them later chose to make artwork that expressed their views.

From there, I suggested that we zero in on gun violence as an issue to discuss further, given that all six groups had identified that as a major issue of concern (and as we had anticipated and as the word map above demonstrated). For an exercise, I gave them each a blank form (stating only “gun violence”) to fill out and asked them to imagine a way in which one act of gun violence could lead to other negative effects and eventually back to gun violence again. As part of the learning goal of the lesson, I wanted them to grasp the ways in which one violent act can reverberate negatively out into a community. I also wanted them to see how violence can sometimes lead to more violence — as a precursor to thinking about ways we could envision breaking the cycle of violence.

Here are three examples of the “cycles of violence” that students generated:

Example #1: “Gun Violence → Someone dies or gets hurt → The family starts to greive, stress, protest, and use achol. Also, drug-addition. → The children’s grades start to drop, and bully other kids because they are sad. Also, stresses them out. → The neighborhood starts to build gangs. And more achol → Gun Violence”

Example #1: “Gun Violence → Someone dies or gets hurt → The family starts to greive, stress, protest, and use achol. Also, drug-addition. → The children’s grades start to drop, and bully other kids because they are sad. Also, stresses them out. → The neighborhood starts to build gangs. And more achol → Gun Violence”

Example #2: “Gun Violence → Somebody gets shot or killed → Then they go to the hospital and try and save them. Also a trial is started and investigated. Family is informed. Grieving. → Outside people / media are informed. People start to feel unsafe, fear. Might get something to make them feel safe. → The Gun percentage increases, protestants, or revenge. People get scared and try to protect themselves. → Gun Violence”

Example #2: “Gun Violence → Somebody gets shot or killed → Then they go to the hospital and try and save them. Also a trial is started and investigated. Family is informed. Grieving. → Outside people / media are informed. People start to feel unsafe, fear. Might get something to make them feel safe. → The Gun percentage increases, protestants, or revenge. People get scared and try to protect themselves. → Gun Violence”

Example #3: “Gun Violence → People die and get hurt leed to orphanage → Make’s people sad.→ Famalies get sadder.→ People get scared and made and that can leed to suicide → Gun Violence”

Example #3: “Gun Violence → People die and get hurt leed to orphanage → Make’s people sad.→ Famalies get sadder.→ People get scared and made and that can leed to suicide → Gun Violence”

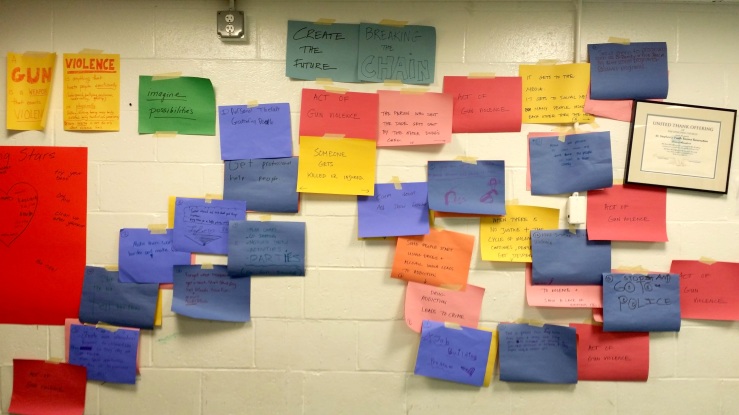

I then compiled all of the students’ individual cycles of violence into one large cycle of violence, which I posted on the wall. For this visual map, used only “warm” colors: red, orange, yellow, pink and called this the FIRE, as a symbol of the destructive potential of gun violence. Then, I gave each student a number, corresponding to a number on the sheets of FIRE and asked them to come up with a solution (which we called “WATER”) to throw on each piece of fire in order to put it out. We put their blue sheets directly over the warm ones, to transform the wall gradually into a sea of blue.

To explain more clearly: each warm-colored FIRE page described one “link” of the chain of violence, taken from the worksheets above (For example: “People get scared and made and that can leed to suicide”). Each blue-colored WATER page initially had only a number written on it (corresponding to the numbers on the wall), but the blue sheet was otherwise completely blank. In small groups of 2-3, students needed to brainstorm ways that the cycle of violence could be broken, at that particular link, through a creative solution. We eventually covered the “fire” completely with our “water” responses.

Here is the wall, mid-stage, as we got closer to putting the fire completely out:

The goal of this exercise was to move past the simplicity of one word or phrase (like “gun violence”) to a more nuanced discussion of the multiple physical and emotional impacts that such violent acts have on a community and the various ways that individuals and communities can constructively respond, as a way to break the vicious cycle. I was impressed by how quickly students brainstormed solutions and how readily they were able to address even the hardest of problems.

To give some examples, some of the proposed “solutions” to break cycles of violence were about personal self-control or managing one’s mental health. It was interesting to me that many of the students drew small pictures to illustrate their ideas, without being asked. The following blue sheet was in response to the problem: “Children start to feel depressed by all the violence.”

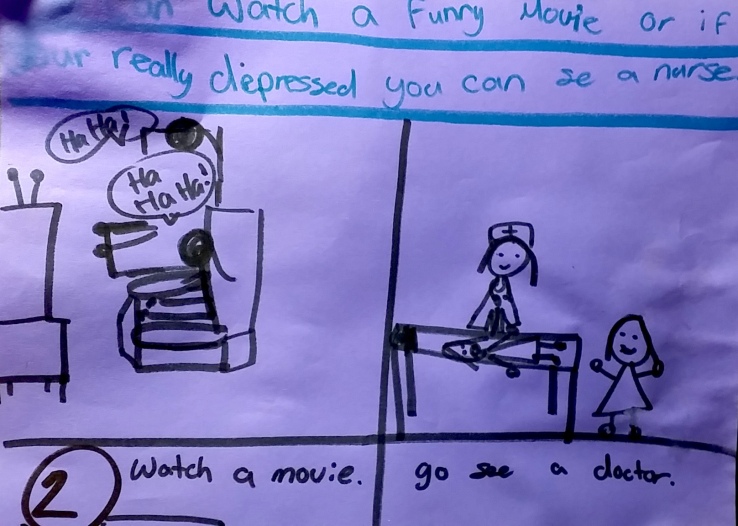

“You can watch a funny movie or if your really depressed you can see a nurse. Watch a movie. Go see a doctor.”

“You can watch a funny movie or if your really depressed you can see a nurse. Watch a movie. Go see a doctor.”

Here are a few other examples of students’ blue “solution” sheets:

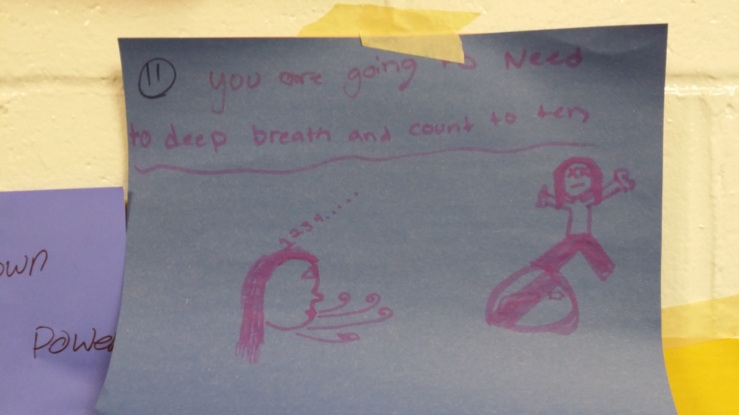

“You are going to need to deep breath and count to ten.”

“You are going to need to deep breath and count to ten.”

Another girl wrote: “Forget what happened, get a book, start studying. Get Friends. (or more PLAYFUL friends). Have fun.”

Other solutions were about different ways the community could respond, including police:

“Create more afterschool programs for children (like B-Ready) so they stay out of trouble. More sports opportunities so they are too preoccupied to join gangs.” (B-Ready is St. Stephen’s afterschool program.)

“Create more afterschool programs for children (like B-Ready) so they stay out of trouble. More sports opportunities so they are too preoccupied to join gangs.” (B-Ready is St. Stephen’s afterschool program.)

“Police need to now the community better. and stop violence. And it lead’s to desperate’chin.”

“Police need to now the community better. and stop violence. And it lead’s to desperate’chin.”

About police responses, another boy wrote: “Police tell people to calm down and don’t hurt the people, just talk to them calmly.”

Another girl wrote: “Tell a police that you don’t feel safe & they can help you. Or instead of buying a gun tell relatives or neibors & they might help & confort you.”

Other responses focused on enacting sensible gun control legislation:

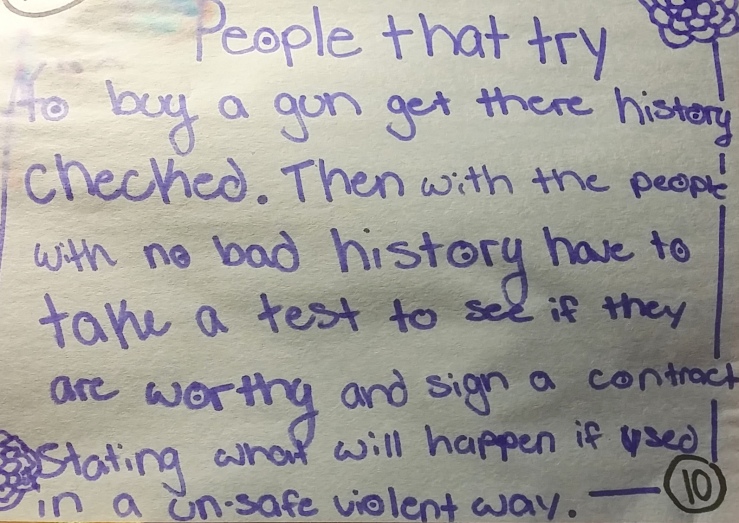

“People that try to buy a gun get there history checked. Then with the people with no bad history have to take a test to see if they are worthy and sign a contract stating what will happen if used in an un-safe violent way.”

“People that try to buy a gun get there history checked. Then with the people with no bad history have to take a test to see if they are worthy and sign a contract stating what will happen if used in an un-safe violent way.”

“There should be more laws against gun-violence and there should be a “happy place” for families who went through it.

“There should be more laws against gun-violence and there should be a “happy place” for families who went through it.

This exercise was designed to give children a sense of agency and hope and help them see that many, small, individual choices can directly affect more peaceful outcomes. It also helped them to see how complex problems, like gun violence, require complex solutions, on the part of both individuals and institutions. The group process of watching a wall filled with dire problems be transformed into a wall of constructive solutions helped us all grapple with a the difficult issue of gun violence without feeling hopeless about how to move forward.

Culminating project:

Mixed media collage paintings that tell a visual story about your community.

We then began our culminating visual art project: creating mixed media collages. Students were asked to “Tell a story about your community. It can be personal or relate to larger issues connected to self, home, school, city, country or world.” I encouraged students to think about both our individual brainstorming sessions and our class discussions to help them identify a story they would like to address. I also discussed with them how a visual story differs from a literal one and how a work of art can also express a feeling or emotion, which then BECOMES the story.

Students used a variety of visual elements to construct their visual stories through collage and painting. I provided ample imagery (literally hundreds of photocopied images) including elements of landscape, cityscape, patterns, faces, objects, etc. to maximize students’ ability to find and create interesting visual juxtapositions. (This is a teaching strategy I learned from my former colleague, Professor Barbara Moody, at Montserrat College of Art.) I asked them to include some kind of human presence, to help create a sense of visual narrative, and discussed the various ways they could do this. We generated some of the imagery ourselves, through cell phone pictures of each other and the surrounding area, and found some images on the Internet. We then cut up, manipulated and recontexualized the images through collage work, acrylic over-painting and glazing with shellac.

As they began working, we discussed art concepts like background, foreground, layering, overlapping, deep space, flat space, offsetting, distortion, emphasis, activating edges, cropping and warm and cool colors. I also explained the history of collage as an art form -the way collage came out of the movement of Synthetic Cubism, whose artists were responding to an ever speedier modern world and a desire to capture that world through incorporating different materials like newspaper, which included the messages found there. We talked about “thinking globally” and how the access to the internet has changed our perception of the world and our understanding of reality. We connected this to visual juxtaposition in collage, and how it can capture some of the complexity of the world we inhabit.

After establishing these basic compositional guidelines and some historical context, we focused again on the idea of narrative. I reiterated that the project theme was “storytelling about your community,” but beyond that was completely free: they could tell whatever visual story they wanted. As their teacher, I felt is was important not to limit their art making to the theme of gun violence (or anything else, for that matter.)

After students created the works, they wrote artist statements in which they connected their artwork to the larger theme of the 2016 B-SAFE summer program – CREATE THE FUTURE. (They were specifically asked to try to respond to the question: “How does your visual story connect to the theme, create the future?”) In so doing, they found meaningful ways to both address difficult issues, and find reason for hope and optimism, looking forward. Like the exercise of putting “water” on the “fire,” this prompt about imagining a connection to the future was an important one. Even when students expressed dark content in their art, they were challenged to seek possible solutions and to imagine relief.

Here is a small selection of final student work, together with their artist statements:

In my artwork, I am depicting a family whose dad was in jail and got shot and it was only the mother and son. People wanted the blacks to be free. It relates to the theme so people can stop using violence. #future. By: O.D. Age: 11

In my artwork, I am depicting a family whose dad was in jail and got shot and it was only the mother and son. People wanted the blacks to be free. It relates to the theme so people can stop using violence. #future. By: O.D. Age: 11

My artwork expresses that now nature is not at its best state (although nature can be beautiful). In the future, nature could be even more beautiful. We can make it more beautiful by not littering and wasting trees and plants. By: J. J. Age: 13

My artwork expresses that now nature is not at its best state (although nature can be beautiful). In the future, nature could be even more beautiful. We can make it more beautiful by not littering and wasting trees and plants. By: J. J. Age: 13

In my artwork, I am depicting Freedom. This relates to the theme Create the Future because a lot of black people are getting killed. So, in the future we could try to make world peace. We could do this by taking away all guns and by people getting a different, bigger heart. By: D.S. Age: 10

In my artwork, I am depicting Freedom. This relates to the theme Create the Future because a lot of black people are getting killed. So, in the future we could try to make world peace. We could do this by taking away all guns and by people getting a different, bigger heart. By: D.S. Age: 10

Even though there is chaos, there is beauty everywhere. By: S.W. Age: 9

Even though there is chaos, there is beauty everywhere. By: S.W. Age: 9

Everyone stop crying, it’s time to go forward. Stop putting on your masks. Go to the future, my children, let the community help the act to build a better future — for our children and city and country and finally, the world. By: J.R. Age: 12

Everyone stop crying, it’s time to go forward. Stop putting on your masks. Go to the future, my children, let the community help the act to build a better future — for our children and city and country and finally, the world. By: J.R. Age: 12

In my visual story, I am showing the feeling of LOVE that hasn’t been loved in years. My artwork is about the world of divorce. In the future, I imagine a more loved world. By: K.N. Age: 10

In my visual story, I am showing the feeling of LOVE that hasn’t been loved in years. My artwork is about the world of divorce. In the future, I imagine a more loved world. By: K.N. Age: 10

My artwork is about a girl that thinks she is ugly and wears a mask to cover it. In the future, I imagine that she doesn’t let anyone bring her down. By: C.C. Age: 11

My artwork is about a girl that thinks she is ugly and wears a mask to cover it. In the future, I imagine that she doesn’t let anyone bring her down. By: C.C. Age: 11

The left side is filled with depression and war. It isn’t till the boat crosses the other side of the new century that there shows a clearer side to life. By: R.V. Age: 12

The left side is filled with depression and war. It isn’t till the boat crosses the other side of the new century that there shows a clearer side to life. By: R.V. Age: 12

In my piece, I express how kids don’t have a say in things. Also, I express how there’s not a lot of food, etc., to go around. In the future, it will be different. There will be a lot of everything. By: A.T. Age: 12

In my piece, I express how kids don’t have a say in things. Also, I express how there’s not a lot of food, etc., to go around. In the future, it will be different. There will be a lot of everything. By: A.T. Age: 12

We have different identities, but we are all brothers and sisters. By: J.M. Age: 10

My collage is about me wearing the brain while thinking of my newborn baby sister. And a shadow of her in the day says to me: “I’ll be alright. I’m fine.” That to me is very sad because she passed away the fifth day after she was born and I couldn’t sleep that night. The worst part ever was that I never got to see her, I only watched her die. And I never got to bring her home. I’ve really suffered in my life. By: J.U. Age: 10

In my visual story, I am showing you slavery from a long time ago when the underground railroad existed. By T. W. Age: 11

In my visual story, I am showing you slavery from a long time ago when the underground railroad existed. By T. W. Age: 11

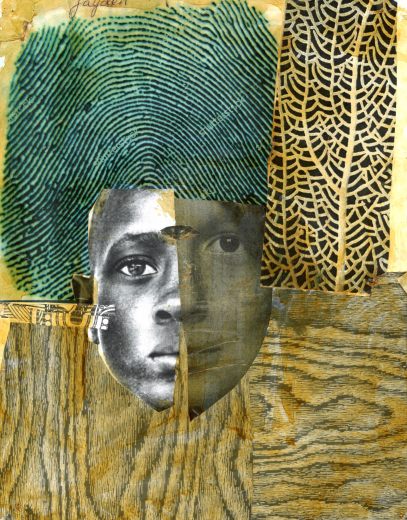

In my visual story, I am showing a young boy and how he feels lost in the world because people keep putting him out of his place, saying that he can’t be in some places (relating to racism, since it’s still alive today). This relates to Create the Future by giving people hope to keep their heads high and don’t let anyone put you down. By: T.S. Age: 11

In my visual story, I am showing a young boy and how he feels lost in the world because people keep putting him out of his place, saying that he can’t be in some places (relating to racism, since it’s still alive today). This relates to Create the Future by giving people hope to keep their heads high and don’t let anyone put you down. By: T.S. Age: 11

These art works speak of struggle, joy, loss, resilience and hope in a powerful and direct way. Their visual stories address both personal and societal issues with force, thoughtfulness and immediacy. I believe that the quality and depth of the work is due in part to the time we spent brainstorming and discussing social justice issues together. Through collaboration, we created a safe, generative context that allowed students to express their feelings and ideas and to feel that their voices mattered. The ideation stages we went through as a group were crucial to setting up the understanding that art can be powerful and can relate to issues students feel are important, whether past or present.

Don’t Be Limited

The range of work and subject matter addressed also demonstrate that young people benefit when given more thematic freedom. We discussed gun violence, but did not limit the art making to gun violence. This was important. When talking about issues, we cast a wide net, even expanding, for example, our discussion to include “global” issues. From my experience, young people connect most deeply to art when they are given complete choice and freedom. For example, during the initial brainstorm on social issues, some students asked me: “Can we really say whatever we want? We’re not going to get into trouble?” (To which I replied, of course: “Yes you can say whatever you want. No, you are absolutely not going to get into trouble.”) Later, I reminded them of this, and said that they could really make art about anything they wanted — any story they wanted to tell. The freedom and power of this approach to art practice is important because it gives full agency over to young people. They sense this agency and respond by taking ownership of both the process and their final product, including their artist statements. As their teacher, I loved the feeling of surprise I experienced when reading their artist statements. Some of them went far beyond any issues or ideas that we had discussed as a group.

Here are three more student examples that illustrate this type of expansive thinking:

In my visual story, I show color coming to all things. Color to me represents beauty and new life. This relates to the future because I believe that we will one day have life on other planets. By: N.J. Age: 13

In my visual story, I show color coming to all things. Color to me represents beauty and new life. This relates to the future because I believe that we will one day have life on other planets. By: N.J. Age: 13

Five warriors made a legendary bird that could rebuild the world. He first made the mountains and then he gave all the people life. Then he gave everything to the people that they needed to live. By: J.G. Age 10

Five warriors made a legendary bird that could rebuild the world. He first made the mountains and then he gave all the people life. Then he gave everything to the people that they needed to live. By: J.G. Age 10

My artwork is about places around the world — from America to Asia — from the forest to food courts to elevators. And it’s about the people who visited those places. By: S.W. Age: 10

My artwork is about places around the world — from America to Asia — from the forest to food courts to elevators. And it’s about the people who visited those places. By: S.W. Age: 10

The B-SAFE program started the summer with the theme Create the Future, taken from a quotation by Mae Jemison, the first African-American female astronaut, “we have the opportunity to create the future and decide what that’s like.” As a guiding idea, this quotation helped us both deal with hard issues and work to imagine more just world. Through the process of making art, however, another one of Mae Jemison’s quotations became increasingly relevant: “Don’t be limited by other’s limited imaginations.” Through their art and artist statements, kids at B-SAFE demonstrated that, when given full artistic freedom, young people can put voice to both the beauty and the injustice around them and teach us how to think more expansively and constructively about the world we share.

[…] Source: “Safe, Big and Connected” and Not Shying Away from Change […]

[…] kind of issues they might want to address. I also took the opportunity to share with them the word maps created by prior students and posed the question: “Comparing your word map of issues to the word map by middle […]